For so many years, Japan has been like a lab experiment for economists, because it perfectly shows exactly what happens when you push financial policies to their limits. Now, as the Bank of Japan (BoJ) considers hiking rates for the first time since the steamy summer of 2006, everyone’s shaking with anticipation. Are they actually gonna do it?

So, here’s the scoop. The BoJ kind of wants to nudge its policy rate from the chilly depths of negative territory into the warm embrace of positive figures. I’m talking about a jump of 20 basis points to a snug 0.1 percent. The people in charge of the central bank are scratching their heads over a few key puzzles though. Should they go straight to zero or jump right into the positives? How do they deal with their Godzilla-sized bond collection? And the billion-yen question:- What’s the game plan after the first rate hike?

Peeking through the curtains, it seems like they’re leaning towards a mild bump to 0.1 percent, as hinted by Shinichi Uchida, the BoJ’s deputy governor. This little push would, theoretically, elevate money market rates from sub-zero up to somewhere between zero and a hint of positive. But of course there’s still the headache of figuring out what to do with their three-tier system for bank deposits, which has been around for about eight years.

Economists like Stefan Angrick from Moody’s suggest that dumping the tiering system might be the way to go, considering it wasn’t part of the scene back when Japan was all about that zero-interest rate vibe. But, as Izuru Kato from Totan Research points out, this could also mean banks would lose interest in playing the short-term money market game unless the BoJ decides to slim down its balance sheet to lessen its overflowing reserves.

And when it comes to their bond portfolio, don’t expect any dramatic moves towards quantitative tightening. The central bank could slowly let the portfolio shrink by exploiting the uneven maturity dates of its bonds while continuing to snap up new ones. This strategy could see about ¥70 trillion ($470 billion) worth of bonds mature in the next few years, offering a subtle way to reduce the portfolio without making any sudden stops in bond purchases.

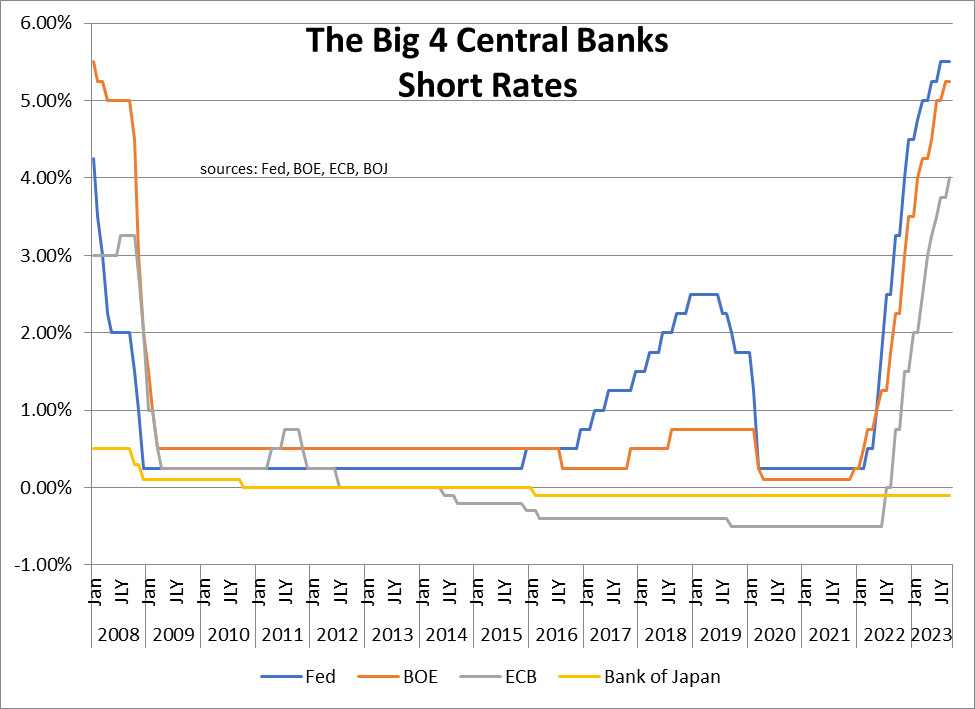

Now, let’s not gaslight ourselves into thinking that Japan’s journey to monetary normalcy will mirror the action-packed adventures of the US Federal Reserve or even the European Central Bank. Japan’s economy barely moved atl all in the past year, inching up by just 0.1 percent in Q4 2023. And the recent inflation spike seems to be cooling off, staying put at the BoJ’s 2 percent target.

This snail-paced growth and inflation outlook means that any rate hikes will likely be few and far between. Uchida himself pointed out that Japan’s situation is a unique beast, especially since the country’s been grappling with deflation and economic stagnation for ages. So, even if the BoJ says “sayonara” to negative rates, maybe don’t expect a rapid series of hikes?

As for wages, there’s a glimmer of hope with large companies hinting at pay bumps. However, the real game-changer would be seeing smaller businesses follow suit. If wages start to climb and inflation eases, Japanese households might finally feel rich enough to splash out more, potentially justifying another rate increase before the year’s out.

Parallel to these economic shenanigans is Japan’s approach to river water control, a nifty metaphor for the BoJ’s monetary policy adjustments. Just as the country is moving away from relying solely on dams and embankments to manage floods, the central bank is tweaking its bond-buying strategy to handle market yields more flexibly.

Last July, the BoJ adjusted its yield curve control program, raising the cap on Japanese government bond yields to 1 percent, aiming to prevent a breach in the financial levees. These tweaks are akin to allowing a controlled overflow to prevent a complete breakdown, indicating a shift towards more adaptable monetary policies.

However, it’s important to understand that these changes don’t signify a complete overhaul of Japan’s monetary framework. The goal remains to steer long-term interest rates in a direction that supports stable prices and wage growth, rather than a wholesale abandonment of existing policies.